Detection of Brucella Antibodies in Dogs From Rural Regions of Hamedan, Iran

Avicenna J Clin Microbiol Infect, 6(4), 122-126; DOI:10.34172/ajcmi.2019.22

Original Article

Detection of Brucella Antibodies in Dogs From Rural Regions of Hamedan, Iran

Jamal Gharekhani1,2*, Alireza Sazmand3

1

Department of Laboratory Sciences, Central Veterinary Laboratory, Iranian Veterinary Organization, Hamedan, Iran.

2

Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran.

3

Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan, Iran.

*Corresponding author:

Jamal Gharekhani,

Central Veterinary Laboratory,

Hamedan Veterinary Office,

Ayatollah-Rafsanjani Street,

Hamedan, Iran ,

Postal Code: 6519611156

Tel: + (98)81 32651801,

Fax: + (98)81 32644474, Email: gharekhani_76@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background: Dogs play a significant role in the maintenance of various pathogens in the environment and their possible transmission to humans. In the case of Brucella spp., infected dogs can shed organisms into the environment via urine and vaginal discharges, and aborted materials or feces. This study aimed to investigate the seroprevalence of Brucella sp. infection in dogs in the rural regions of Hamedan, western Iran.

Methods: Between June and November 2018, Blood samples were obtained from cephalic or saphenous veins of 180 stray dogs from 6 rural regions of Hamedan during June and November 2018. The sera samples were evaluated for the presence of antibodies against Brucella spp. using Rose Bengal plate test (RBT) and Wright’s serum agglutination test (Wright SAT).

Results: Seroprevalence rate of Brucella infection was 3.3% by RBT. (6/180; 95% CI: 0.7%–5.9%). All of the serum positive dogs had titers of 1:80 by Wright SAT. The seropositivity was 3.1% in males, 3.4% in females, 3.2% in <1-year-old, 1.8% in 1–2-year-old, and 4.9% in >2-year-old dogs. No statistically significant correlation was found between the infection rate and gender of dogs (P=0.907) or age groups (P=0.772).

Conclusions: The presence of infected dogs in rural regions is an important risk factor for the transmission of Brucella to humans and livestock. It is suggested that villagers, shepherds, and their families especially children should be provided with the information about risks of getting infection when handling an infected dog.

Keywords: Brucellosis, Serology, Dog, Zoonosis, Hamedan

Background

Dogs play an important role in the maintenance and transmission of several zoonotic pathogens. In the case of Brucella spp., the close contact of dogs with humans and livestock might cause zoonotic diseases and economic losses due to abortions and stillbirths in animals (1,2). Brucellosis is prevalent in some regions of Iran including Hamedan where recently the first human case of infection with Brucella canis in the country was reported (3,4).

Canine brucellosis caused by B. canis, a Gram-negative facultative intracellular bacterium, is a neglected zoonosis. B. canis in dogs was firstly reported in the United States in 1966, and since then the bacterium has been detected globally, presenting itself in various forms (1,5). The predominant signs of disease in dogs, the major hosts, are abortion, infertility, stillbirth, lymphadenitis, epididymitis, orchitis, and prostatitis (2). Transmission of infection occurs via ingestion of contaminated materials or venereal routes. Diagnosis is usually based on the isolation of causative agent and/or serology techniques (6). B. canis has been reported in humans and wild canids, as well (7). Although B. canis is the important cause of brucellosis in dogs, infection with B. abortus, B. melitensis , and B. suis has also been reported (8). Considering that infected dogs can shed organisms into the environment via urine and vaginal discharges and secretions, aborted materials or feces, they play a significant role in the maintenance of Brucella spp. and its possible transmission to other dogs, cattle, and humans (8,9).

In an earlier research from Hamedan, the rate of brucellosis was detected 3% and 4.6% in sheep and goats, respectively (10). Moreover, seroprevalence rates of 8.1% in veterinarians, 15% in slaughterhouse workers, and 17% in butchers have been reported (11). The incidence rate of human brucellosis in Hamedan province is 31–41 per 100 000 population, which is classified as “very high” in Iran (12). Recurrence rate of human brucellosis in this region is calculated as 6.45% (13) and direct contact of human with infected animals is the main risk factor for the disease (4,11,12,14).

In Iran, there is scanty knowledge about canine brucellosis with no information from Hamedan. Therefore, the aim of the current cross-sectional study was to determine the rate of Brucella sp. infection in dogs from Hamedan, West part of Iran. Furthermore, a historical mini-review on the available literature on Brucella infection in dogs of Iran was presented in the discussion section.

Methods

Study Region, Animals, and Serum Collection

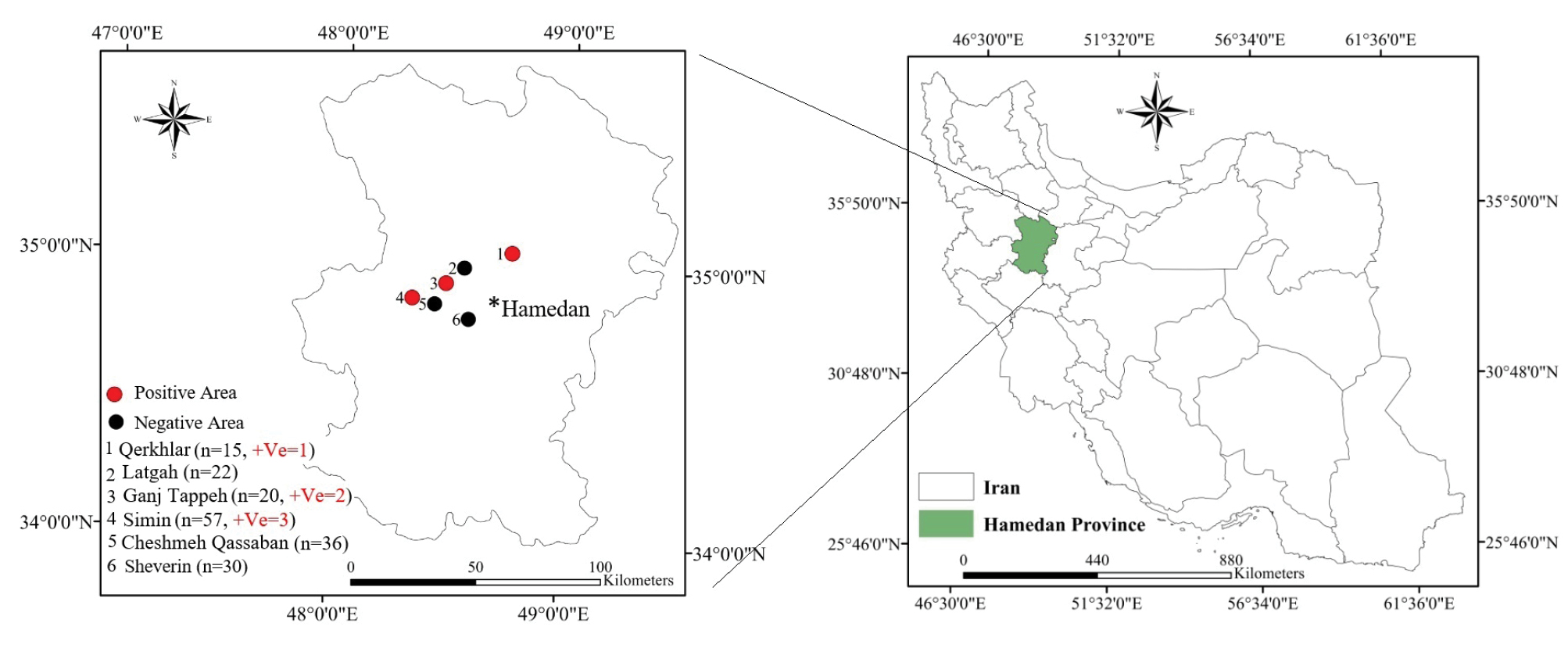

Between June and November 2018, Blood samples were obtained from cephalic or saphenous veins of 180 stray dogs from six rural regions of Hamedan namely Qerkhlar, Latgah, Ganj Tappeh, Simin, Cheshmeh Qassaban, and Sheverin during June and November 2018 (Figure 1). Blood samples from Ganj Tappeh and Cheshmeh Qassaban were collected for another study (15) and the rest were taken for routine surveillance program of Iranian Veterinary Organization. Sex and age of dogs were recorded in individual data forms. Dogs were categorized based on their age in three groups of less than 1-year-old, between 1 and 2 years old and more than 2 years old. The sera were separated by centrifuging the blood samples at 1000 ×g for 10 minutes and stored at –20°C until laboratory examination.

Location of Sampled Regions in Hamedan

Rose Bengal Plate Test

Initially the sera were screened for the presence of anti- Brucella antibodies using Rose Bengal plate test (RBT), which is a routine qualitative test for brucellosis in both humans and animals. The antigens that were purchased from Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute, Iran, could detect B. abortus, B. melitensis , and B. suis.

For the test, 30 μL of RBT antigen (Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute, Iran) and 30 μL of serum sample were placed on a white ceramic tile, mixed using sterile applicator stick, rocked gently for 4 minutes, and monitored for agglutination. The formation of distinct pink granules (agglutination) was recorded as positive (6). The RBT positive samples were further evaluated using Wright serum agglutination test.

Wright serum agglutination test (Wright SAT)

For the first tube, 0.8 mL of physiological saline solution was dispensed while 0.5 mL of the solution was transferred to the second, third, fourth, and fifth tubes. Then, 0.2 mL of the test serum was added to the first tube and mixed properly. Serial dilution was then carried out by pipetting 0.5 mL of the mixture in the first tube to the second tube. This procedure continued until the fifth tube. The final 0.5 mL from the fifth tube was discarded. Finally, 0.5 mL of the antigens (Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute, Iran) was added to all the tubes. The tubes were covered, shaken, and incubated at 37°C for 20 hours. Agglutination titers were determined according to positive and negative controls (10,16).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Chi-square test (χ2) with a confidence interval (CI) of 95% (SPSS 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Based on the screening results by RBT, the rate of Brucella infection was found in 3.3% (6/180; 95% CI: 0.7%–5.9%) of animals. Six seropositive dogs were from Qerkhlar (n=1), Ganj Tappeh (n=2), Simin (n=3) regions (Figure 1). All of the positive dogs had a titer of 1:80 antibodies according to Wright SAT. No statistically significant difference was observed between infection rate and gender (P =0.907) or age groups, (P =0.772) (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Seroprevalence of Brucella sp. Infection in Dogs From Hamedan According to Different Sexes and Age Groups

|

|

No. of Dogs (%)

|

No. of Seropositive Dogs (%)

|

Statistical Analyses

|

| Gender |

|

|

χ2= 0.013, P =0.907 |

| Male |

64 (35.6) |

2 (3.1) |

|

| Female |

116 (64.4) |

4 (3.4) |

|

| Age groups (y) |

|

|

χ2= 0.516, P =0.772 |

| <1 |

63 (35) |

2 (3.2) |

|

| 1-2 |

56 (31.1) |

1 (1.8) |

|

| >2 |

61 (33.9) |

3 (4.9) |

|

Discussion

In this study, sera of 180 dogs from Hamedan province were tested for brucellosis using RBT and Wright SAT assays. Six (3.3%) dogs reacted positive with titers of 1:80. Tadjebakhche and Gatel (17) were the first who tested canine blood sera for brucellosis in Iran in 1972. Since then, several serological studies were performed in various regions, employing different diagnostic techniques (Table 2) (17-29). Seroprevalence of brucellosis in the present study (3.3%) was in the range of that previously reported from Iran (Table 2). Differences in the incidence of canine brucellosis in Hamedan compared to other regions of Iran could be attributed to climatic differences. Furthermore, farmers’ knowledge about brucellosis has significantly increased in recent years; this has led to less exposure of stray dogs to livestock and their aborted foetuses. The role that dogs play in the incidence of human brucellosis is unclear in Iran due to lack of comprehensive reports in this field. However, seropositivity of dogs with zoonotic Brucella species indicate the possibility of transmission of these bacteria from dogs to humans, as well as farm animals in the region.

|

Table 2. Serological Studies on Canine Brucellosis in Iran From 1972 Onward

|

|

Area

|

Year

a

|

No. of Tested Dogs

|

Method(s): No. of Positive Cases (%)

|

Reference

|

| Tehran |

1972 |

41 |

Wrightb + CFTc: 2 (4.9%) |

(17) |

| Tehran and Karaj |

1975 |

225 |

Card test: 6 (2.7%) |

(18) |

|

|

|

Wright: 6 (2.7%) |

|

|

|

|

CFT: 5 (2.2%) |

|

| Shiraz |

1996 |

228 |

RBTd + Wright + 2-MEe: 2 (0.88%) |

(19) |

|

|

|

Brucella isolation: unsuccessful

|

|

| Tabriz |

1996 |

112 |

RBT: 23 (20.5%) |

(20) |

|

|

|

Wright: 19 (16.9%) |

|

|

|

|

2-ME: 7 (6.2%) |

|

|

|

|

Brucella isolation: 4 (3.6%)

|

|

| Mashhad |

1997 |

100 |

RBT: 38 (38%) |

(21) |

|

|

|

Wright: 21 (21%) |

|

|

|

|

2-ME: 18 (28%) |

|

| Mashhad |

2003 |

280 |

RBT: 15 (5.35%) |

(22) |

|

|

|

Wright: 13 (4.64%) |

|

|

|

|

2-ME: 2 (0.71%) |

|

| Neyshabur |

2007 |

50 |

RBT: 9 (18%) |

(23) |

|

|

|

Wright: 2 (4%) |

|

| Ahvaz |

2009 |

102 |

Rapid B. canis Ab test kit: 5 (4.9%) |

(24) |

| Ahvaz |

2010 |

116 |

Rapid B. canis Ab test kit: 12 (10.3%) |

(25) |

| Markazi |

2011 |

110 |

RBT: 6 (5.4%) |

(26) |

|

|

|

Wright: 6 (5.4%) |

|

|

|

|

2-ME: 4 (3.6%) |

|

| Shiraz |

2011 |

175 |

RBT: 51 (29.1%) |

(27) |

|

|

|

Wright: 51 (29.1%) |

|

| Urmia |

2017 |

256 |

NSf: 28 (10.9%) |

(28) |

| Mashhad |

2019 |

173 |

ELISA IgG: 34 (19.6%) |

(29) |

| Hamedan |

|

180 |

RBT: 6 (3.3%) |

This study |

|

|

|

Wright: 6 (3.3%) |

|

|

a Year of publication; b Wright’s serum agglutination test; c Complement fixation test; d Rose Bengal test; e 2-mercaptoethanol Brucella agglutination test; f Not stated.

|

In this study, specific B. canis antibodies could not be investigated; however, in Ahvaz city, 102 blood samples from companion dogs were examined using a commercial Rapid Canine Brucella Ab Test Kit® (Bionote, South Korea), from which 4.9% were found infected (25). In a study conducted in Fars province using the same kit, 10.6% of examined dogs reacted positive (30). Moreover, in Kerman province, seropositivity to B. canis was detected 15.8% using an immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) test kit (MegaFLUO® BRUCELLA canis, Megakor, Austria) (16). This rate was 20.9% in São Paulo, Brazil (using blood culture method), 4.9% in Mississippi, USA (using rapid serology method), and 4.4% in South Africa (using 2-mercaptoethanol-tube agglutination test) (5,6,31). Regarding the fact that rapid diagnostic kits and IFA slides for B. canis are not imported to Iran regularly, it is suggested that Iranian researchers focus on the domestic production of such diagnostic kits.

In the only PCR-based study in Iran, 14 out of 94 (14.9%) tested blood samples from companion dogs of Isfahan and Shahrekord cities were reported to be positive by conventional-PCR (32). As the PCR products in the latter study were not confirmed by nucleotide sequencing and the dogs did not show any sign of brucellosis, these results should be taken with caution. More recently, DNA of Brucella sp. was detected in vaginal swabs of 3 out of 70 (4.3%) dogs referred to a teaching hospital in Kerman (33).

In this study, no statistical correlation was found between the age of dogs and seropositivity. Conversely, in previous studies (25,30,31), higher seroprevalences were detected in older dogs which could be due to the fact that an increase in age of dogs has a direct relationship with the probability of infection via mating and coming into contact with infectious materials (31).

Generally female dogs pose a greater risk to humans as Brucella organisms are shed in the birth fluids and vaginal discharges (31). However, similar to previous findings, no significant correlation was observed between the development of infection and gender of dogs (16,25,30), showing that both sexes appear to be equally susceptible (31,34).

Conclusions

Although the seroprevalence of Brucella sp. was not high in Hamedan, further screening programs on dog population and designing a plan for control of infection is highly recommended in different regions of Iran. The presence of infected dogs in rural regions is an important risk factor for the transmission of disease to livestock causing economic losses due to abortions and stillbirths. It is suggested that villagers, shepherds, and their families especially children should be provided with the information about risks of getting infection when handling an infected dog.

Ethical Approval

Blood samples were taken from dogs after getting official permission and under supervision of Institutional Animal Ethics and Research Committee of Iranian Veterinary Organization (IVO, Iran), Hamedan Office (Certificate No. 32/1397.4.1).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None.

Funding

This study was partially supported by Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan, Iran.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Mr. Ehsan Abbasi-Doulatshahi and Dr. Ehsan Barati from Hamedan Veterinary Office, for their assistance in the laboratory works.

References

- Wanke MM. Canine brucellosis. Anim Reprod Sci 2004;82-83:195- 207. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.05.005. [Crossref]

- Hensel ME, Negron M, Arenas-Gamboa AM. Brucellosis in dogs and public health risk. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24(8):1401-6. doi: 10.3201/eid2408.171171. [Crossref]

- Majzoobi MM, Ghasemi Basir HR, Arabestani MR, Akbari S, Nazeri H. Human brucellosis caused by Brucella canis: a rare case report. Arch Clin Infect Dis 2018;13(5):e62776. doi: 10.5812/archcid.62776. [Crossref]

- Eini P, Keramat F, Hasanzadehhoseinabadi M. Epidemiologic, clinical and laboratory findings of patients with brucellosis in Hamedan, west of Iran. J Res Health Sci 2012;12(2):105-8.

- Keid LB, Chiebao DP, Batinga MCA, Faita T, Diniz JA, Oliveira T, et al. Brucella canis infection in dogs from commercial breeding kennels in Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis 2017;64(3):691-7. doi: 10.1111/ tbed.12632. [Crossref]

- Hubbard K, Wang M, Smith DR. Seroprevalence of brucellosis in Mississippi shelter dogs. Prev Vet Med 2018;159:82-6. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2018.09.002. [Crossref]

- Esmaeili H. Brucellosis in Islamic republic of Iran. J Med Bacteriol 2014;3(3-4):47-57.

- Baek BK, Lim CW, Rahman MS, Kim CH, Oluoch A, Kakoma I. Brucella abortus infection in indigenous Korean dogs. Can J Vet Res 2003;67(4):312-4.

- Forbes LB. Brucella abortus infection in 14 farm dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1990;196(6):911-6.

- Gharekhani J, Rasouli M, Abbasi-Doulatshahi E, Bahrami M, Hemati Z, Rezaei A, et al. Sero-epidemiological survey of brucellosis in small ruminants in Hamedan province, Iran. J Adv Vet Anim Res 2016;3(4):399-405.

- Mamani M, Majzoobi MM, Keramat F, Varmaghani N, Moghimbeigi A. Seroprevalence of brucellosis in butchers, veterinarians and slaughterhouse workers in Hamedan, western Iran. J Res Health Sci 2018;18(1):e00406.

- Golshani M, Buozari S. A review of brucellosis in Iran: epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis, control, and prevention. Iran Biomed J 2017;21(6):349-59. doi: 10.18869/acadpub.ibj.21.6.349. [Crossref]

- Nematollahi S, Ayubi E, Karami M, Khazaei S, Shojaeian M, Zamani R, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of human brucellosis in Hamedan province during 2009-2015: results from the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Int J Infect Dis 2017;61:56- 61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.06.002. [Crossref]

- Keramat F, Karami M, Alikhani MY, Bashirian S, Moghimbeigi A, Adabi M. Cohort profile: Famenin brucellosis cohort study. J Res Health Sci 2019;19(3):e00453.

- Greco G, Sazmand A, Goudarztalejerdi A, Zolhavarieh SM, Decaro N, Lapsley WD, et al. High prevalence of Bartonella sp. in dogs from Hamedan, Iran. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2019;101(4):749-52. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0345. [Crossref]

- Akhtardanesh B, Ghanbarpour R, Babaei H, Nazeri M. Serological evidences of canine brucellosis as a new emerging disease in Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2011;1(3):177-80. doi: 10.1016/S2222- 1808(11)60023-6. [Crossref]

- Tadjebakhche H, Gatel A. Incidence sérologique des anticorps anti-brucelliques chez les animaux domestiques de l’homme en Iran. Rev Elev Med Vet Pays Trop 1972;25(4):521-5. doi: 10.19182/ remvt.7773. [Crossref]

- Montazerolghaem F. Serological study of brucellosis in dogs [dissertation]. Tehran: University of Tehran; 1975. [Persian].

- Sadighi M. Serological survey of Brucella infection in dogs of Shiraz and suburban areas. In: Proceedings of 3rd Congress of Zoonoses; 23–25 April 1996; Mashhad, Iran. p. 90. [Persian].

- Rezaei-Sadaghiani R, Zowghi E, Marhemati-Khamene B, Mahpeikar H. Brucella melitensis infection in sheep-dogs in Iran. Arch Razi Inst 1996;46-47(1):1-7. doi: 10.22092/ari.1996.109149. [Crossref]

- Talebkhan Garoussi M, Firoozi S, Nourouzian I. The serological survey of Brucella abortus and melitensis in shepherd dogs around Mashhad farms. J Fac Vet Med Univ Tehran 1997;51(2):55-65. [Persian].

- Sardari K, Kamrani AR, Kazemi KH. The Serological survey of Brucella abortus and melitensis in stray dogs in Mashhad, Iran. In: Proceedings of 28th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association; 24–27 October 2003; Bangkok, Thailand.

- Mashhadi-Rafiee S, Ale-Davood SJ, Najjar M. Seroepidemiological study of brucellosis in sheepdogs in Neyshabur County. J Vet Microbiol 2007;3(1):1-6. [Persian].

- Mosallanejad B, Ghorbanpoor Najafabadi M, Avizeh R, Mohammadian N. A serological survey on Brucella canis in companion dogs in Ahvaz. Iran J Vet Res 2009;10(4):383-6. doi: 10.22099/ijvr.2009.1731. [Crossref]

- Mosallanejad B, Ghorbanpoor Najafabadi M, Avizeh R, Mohammadian N. Seroprevalence of Brucella canis in rural dogs in Ahvaz area. Iran Vet J 2010;5(4):35-43. [Persian].

- Ganji A, Hosseini SS, Banasaz A, Rezaei R, Rahimi S, Esna-Ashari H. Seroepidemiological study of brucellosis in sheepdogs in Markazi province. In: Proceedings of the 4th National Iranian Congress of Brucellosis; 13–15 December 2011; Tehran, Iran. p. 162-3. [Persian].

- Bigdeli M, Namavari MM, Moazeni-Jula F, Sadeghzadeh S, Mirzaei A. First study prevalence of brucellosis in stray and herding dogs south of Iran. J Anim Vet Adv 2011;10(10):1322-6. doi: 10.3923/ javaa.2011.1322.1326. [Crossref]

- Salimi-Rad M, Ghaffari R, Mahd-Gharehbagh P. Serological survey of brucellosis in dog population of Urmia. In: Proceedings of the First National Congress on Zoonoses; 22–23 February 2017; Esfahan, Iran. [Persian].

- Kheradmand N. Preliminary serological investigation of Brucella canis in dogs of Mashhad [dissertation]. Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad; 2019. [Persian].

- Behzadi MA, Mogheiseh A. Epidemiological survey of Brucella canis infection in different breeds of dogs in Fars province, Iran. Pak Vet J 2011;32(2):234-6.

- Oosthuizen J, Oguttu JW, Etsebeth C, Gouws WF, Fasina FO. Risk factors associated with the occurrence of Brucella canis seropositivity in dogs within selected provinces of South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc 2019;90(0):e1-e8. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v90i0.1956. [Crossref]

- Khamesipour F, Doosti A, Fard Emadi M, Awosile B. Detection of Brucella sp. and Leptospira sp. in dogs using conventional polymerase chain reaction. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy 2014;58(4):527-31. doi: 10.2478/bvip-2014-0081. [Crossref]

- Hassan-Abadi N. Evaluation of the presence of Brucella bacteria in vaginal swab samples collected from dogs referred to the Hospital of Faculty of Veterinary Medicine [dissertation]. Kerman: Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman; 2018. [Persian].

- Bamaiyi PH. Prevalence and risk factors of brucellosis in man and domestic animals: a review. Int J One Health 2016;2:29- 34. doi: 10.14202/ijoh.2016.29-34. [Crossref]