Avicenna Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 8(2):51-56.

doi: 10.34172/ajcmi.2021.10

Original Article

Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Loaded Antibiotics Against Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter spp.

Behnaz Shokrollahi 1  , Akram Sadat Tabatabaee Bafroee 1, *

, Akram Sadat Tabatabaee Bafroee 1, *  , Tayebeh Saleh 1

, Tayebeh Saleh 1

Author information:

1Department of Biology, East Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

*

Corresponding author: Akram Sadat Tabatabaee Bafroee, East Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qiam Dasht, Tehran, IRAN, Postal code: 1866113118, Tel: +982133594950-9, Fax: +982133586330. Email:

akram_tabatabaee@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background: Metal oxide nanoparticles (NPs) have shown promising efficacy for combating bacterial resistance due to their antibacterial properties. This research investigated the effect of zinc oxide NPs (ZnO-NPs) on the antibacterial activity of conventional antibiotics including ciprofloxacin (CIP), cefotaxime (CTX), and colistin (CST) against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter isolates.

Methods: The disc diffusion method was performed to detect the pattern of antibiotic resistance in isolates. The synthesized ZnO-NPs via the solvothermal method were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Finally, the broth microdilution technique was conducted to demonstrate the antibacterial activity of CIP, CTX, and CST antibiotics with and without a sub-inhibitory concentration of ZnO-NPs.

Results: XRD, EDS, and FESEM results confirmed the crystalline structure of ZnO-NPs, and the average size was 100±58.68 nm. All isolates were discovered to be of multidrug-resistant (MDR) type and fully susceptible to CST. The antibacterial activity of CTX and CIP was restored when combined with a sub-inhibitory level of ZnO-NPs (0.25 mg/L), and the highest activity was obtained at the concentrations of 32 µg/mL CTX and 8 µg/ mL CIP. Eventually, ZnO-NPs showed a synergistic effect on the antibacterial properties of CST against MDR Acinetobacter.

Conclusions: This research indicated that the combination of ZnO-NPs with some common antibiotics can be considered as a novel strategy for reducing the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Keywords: Resistant Acinetobacter, Zinc Oxide nanmaterials, Ciprofloxacin, Cefotaxime, Colistin, Synergistic effect

Copyright and License Information

© 2021 The Author(s); Published by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited.

Background

Acinetobacter species, gram-negative coccobacilli, are widely distributed in environmental sources such as soil and water. They are the most prevalent cause of hospital-acquired infections, particularly in the intensive care unit (ICU) and their important risk factors are long-term use of antibiotics, long stay in ICU, and serious underlying diseases. In addition, this genus includes a number of taxa among which, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, A. baumannii, A. pilli, and A. nosocomialis have similar genetic and phenotypic properties. They have more recently become a major cause of concern in clinical practices because of their increased high range of resistance to the most commonly used antibiotics (1-3). Oxyimino cephalosporins (e.g., cefotaxime, CTX) and fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, CIP) are the most prevalent antibiotics for controlling infections caused by Acinetobacter species although resistance to these antibiotics is increasing (4). Colistin (CST) is one of the latest therapeutic alternatives for the treatment of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter infections. However, some publications have shown that it is extremely nephrotoxic and resistance to this antibiotic has recently emerged based on evidence (3,5). Therefore, it is urgently needed to discover substances with stronger and more effective antibacterial activity against such MDR bacteria.

The antimicrobial activity of the nanoparticulate form of several metals, metal oxides, metal halides, and bimetals has been well-documented by several researchers as bacteria are hardly resistant to these metals (6-9). Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) are one of the most widely used particles in nanobiotechnology and are of great importance due to their antibacterial properties. ZnO is biologically safe, exhibiting significant antibacterial activity against a wide range of bacterial species when its size decreases to the nanoscale (4,10-13). Their major antibacterial mechanisms have been ascribed to the reactive oxygen species production, lipid peroxidation, and membrane release of reduced sugars, proteins, and DNA (14). ZnO-NPs are frequently toxic to pathogenic bacteria while several studies reported that they are non-toxic to human cells, highlighting the necessity of assessing their application as antibacterial agents in the pharmaceutical industry (10,15). The use of metal NPs in combination with conventional antibiotics may have a synergistic influence due to the simultaneous presence of antibiotics and metal ions released from the NP (4,11,16). More importantly, the antibacterial agent may be applied in extremely lower doses in combination than when administered alone, and thus helping in overcoming the problems of resistance and adverse side effects (16). Accordingly, this study focused on evaluating the possible effect of ZnO-NPs to either regenerate or improve the antimicrobial activity of CIP, CTX, and CST against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter.

Methods

All the chemicals and media were prepared from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). The antibiogram discs were purchased from the MAST Company, UK. No human was involved in this descriptive study, and Acinetobacter isolates were acquired from discarded clinical microbiology plates collected during the diagnostic testing of Day Hospital, Tehran, Iran. The isolates were grown on brain heart infusion agar for 24-48 hours at 35°C. Their purity and identity were confirmed by macroscopic, microscopic, and standard biochemical methods.

Fabrication of ZnO Nanofluids

ZnO-NPs were synthesized using the solvothermal process according to the protocol represented by Ashtaputre et al (17). To stabilize ZnO nanofluids for antimicrobial assessments, glycerol and ammonium citrate were applied as the base fluid and dispersant, respectively. ZnO-NPs and ammonium citrate, with equal ratios, were completely mixed with glycerol solution by a magnetic stirrer at ambient temperature for 24 hours (18).

ZnO -NPs Characterization

The synthesized ZnO-NPs were characterized by several techniques. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were used to determine the crystal structure of NPs. The XRD was accomplished at ambient temperature using an analytical X-Pert Pro diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å, voltage: 40 kV, current: 40 mA) and in the range of 10°-90° (2Ө) at an angular speed of 0.02°/s. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM Zeiss Sigma VP FE-SEM) on gold-coated samples was applied to identify the morphology of ZnO-NPs. Further verification was performed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis, which demonstrates the existence of Zn in the intended NPs (19).

Determination of the Antibiotic Resistance Profile in Acinetobacter Isolates

The disc diffusion technique was performed for all isolates in accordance with the CLSI 2017 protocol (20). Mueller Hilton agar plates were seeded with 100 µL of the standardized bacterial inoculum corresponding to the 0.5 McFarland turbidity (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL). The common antibiotic discs were placed onto the Mueller-Hilton agar plates and incubated at 35°C for 18 hours. These antibiotic discs included ticarcillin (TIC, 75 μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 µg), CTX (30 µg), cefoxitin (30 µg), CST (10 µg), aztreonam (30 µg), meropenem (MEM, 10 μg), imipenem (10 µg), tigecycline (15 μg),rifampin (5 μg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg),amikacin (30 μg),gentamicin (10 µg),chloramphenicol (30 µg),andazithromycin (15μg).Further, other included discs were ampicillin-sulbactam (SAM,10/10 μg), amoxycillin/clavulanic acid (AMX/CLV, 30/10),teicoplanin(30 µg),piperacillin (PIP, 100 μg), CIP (5 µg), vancomycin (30 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), and tobramycin (10 µg). The inhibition zone diameter (mm) was measured, and the resistance profile of the isolates was determined via the CLSI standard table, and finally, Acinetobacter ATCC 19606 was employed as a standard.

Evaluation of the Effect of ZnO -NPs With Antibiotics (i.e., CIP, CTX, and CST) Against Multidrug-Resistant Isolates

Based on the antibiotic resistance pattern, CTX, CIP, and CST were selected for the next experiments. Then, the broth microdilution method was conducted according to the applied procedure by Balouiri et al (21) to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Briefly, a two-fold dilution of ZnO-NPs (0.0625-2 mg/mL), CTX (2-64 µg/mL), CIP (1-16 µg/mL), and CST (0.5-16 µg/mL) was prepared in 100 µL of Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) in the wells of each row in a microtiter plate. Next, each well was inoculated with 50 μL of standardized microbial inoculum equal to the 0.5 McFarland turbidity. The microtiter plates were incubated at 35°C for 18-24 hours. The turbidity of all wells was determined at 630 nm using an ELSA microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, USA) every 2 hours. In addition, the growth of isolates was assayed in an ammonium citrate/glycerol mixture lacking ZnO-NPs. The antibiotic concentrations were calculated by Eq. (1) as follows:

(2)

To assess the effect of ZnO-NPs on restoring and improving the antibacterial properties of common antibiotics, isolates were exposed to various concentrations of CAZ (16-64 µg/mL), CIP (4-16 µg/mL), and CST (0.5-2 µg/mL) combined with the sub-inhibitory concentration of ZnO-NPs (1/2 MIC, 0.25 mg/mL) for 24 hours. The growth of isolates was evaluated based on the aforementioned method. Additionally, the inoculated MHB, free of ZnO-NPs and antibiotic, was considered as a positive control. The antibacterial effectiveness was represented as the MIC and the mean of growth inhibition percentage (GI%) according to the positive control growth. GI% for each concentration was determined by Eq. (2) as (4,22):

(2)

Statistical Analysis

In this study, all outcomes were expressed as mean values with their standard deviations (mean ± SD). SPSS 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s tests were applied for statistical data analyses and multiple comparisons, respectively. All tests were performed in triplicate, and the level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern

Data on the antimicrobial resistance frequency of Acinetobacter isolates are presented in Table 1. All isolates showed a considerable level of resistance to the most tested antibiotics. Full resistance was determined against TIC, MEM, PIP, CTX, CIP, AM, and, AMX/CLV acid meanwhile full susceptibility was observed to CST. Moreover, all isolates represented to be resistant to different classes of antibiotics. CST, CTX, and CIP were selected for the following experiments.

Table 1.

The Frequency of Antibiotic Resistance Among Acinetobacter Isolates

|

Antimicrobial Agent (µg)

|

Abbreviation

|

Acinetobacter

Isolates

(n=23)

|

Sensitive

% (n)

|

Resistant

% (n)

|

| Ticarcillin (75) |

TIC |

0 (0) |

100 (23) |

| Aztreonam (30) |

ATM |

4.35 (1) |

95.65 (22) |

| Meropenem (10) |

MEM |

0 (0) |

100 (23) |

| Tigecycline (15) |

TGC |

95.65 (22) |

4.35 (1) |

| Colistin (10) |

CT |

100 (23) |

0 (0) |

| Rifampin (5) |

+RA |

73.91 (17) |

26.09 (6) |

| Azithromycin (15) |

AZM |

26.09 (6) |

73.91 (17) |

| Teicoplanin (30) |

TEI |

34.78 (8) |

65.22 (15) |

| Piperacillin (100) |

PIP |

0 (0) |

100 (23) |

| Vancomycin (30) |

VAN |

13.04 (3) |

86.96 (20) |

| Chloramphenicol (30) |

C |

13.04 (3) |

86.96 (20) |

| Levofloxacin (5) |

LVX |

13.04 (3) |

86.96 (20) |

| Tobramycin (10) |

TOB |

26.09 (6) |

73.91 (17) |

| Cefalotin (30) |

CF |

4.35 (1) |

95.65 (22) |

| Cefotaxime (30) |

FOX |

0 (0) |

100 (23) |

| Ceftazidim (30) |

CAZ |

4.35 (1) |

95.65 (22) |

| Imipenem (10) |

IPM |

4.35 (1) |

95.65 (22) |

| Gentamicin (10) |

GM |

13.04 (3) |

86.96 (20) |

| Ampicillin (10) |

AM |

0 (0) |

100 (23) |

| Ciprofloxacin (5) |

CIP |

0 |

100 (23) |

| Amikacin (30) |

AN |

17.39 (4) |

82.61 (19) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (25) |

SXT |

13.04 (3) |

86.96 (20) |

| Amoxycillin/clavulanic acid (30/10) |

AMX/CVA |

0 (0) |

100 (23) |

ZnO -NPs Characterization

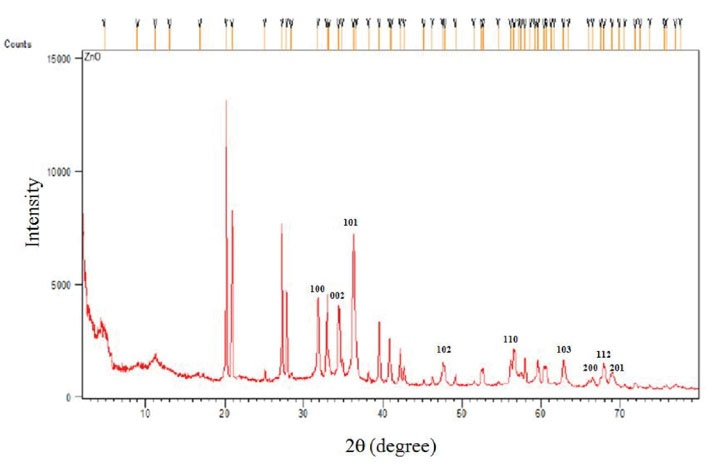

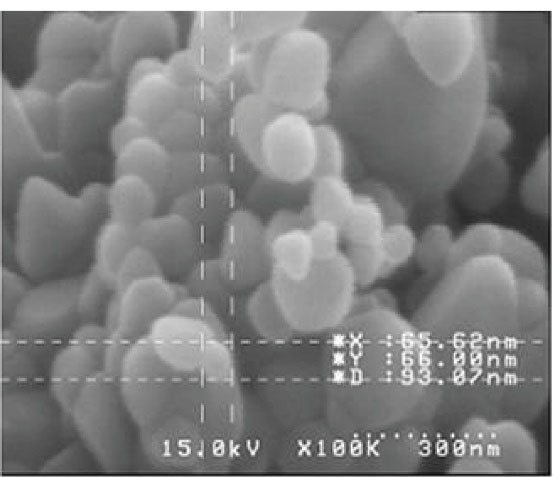

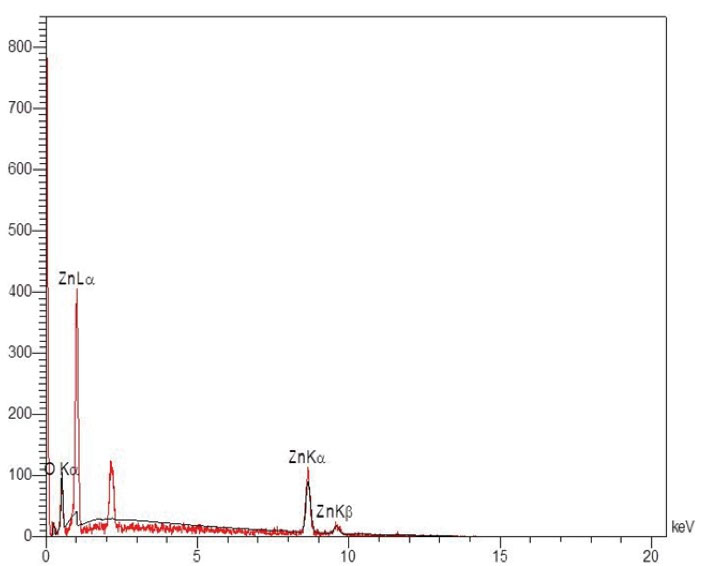

Figure 1 illustrates the XRD pattern of the synthesized ZnO-NPs that confirms the crystalline nature of this NP. A number of strong Bragg reflections can be observed that are correlated with the (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), and (201) reflections of the wurtzite hexagonal phase of ZnO-NPs. Figure 2 depicts the FESEM images of ZnO-NPs. It is obvious that the NPs have spherical shapes with smooth surfaces and an average size of 100±58.68 nm. The EDS data analysis of the ZnO-NPs was implemented by field emission EDS. Table 2 presents the outcomes of the elemental weight percentages of the ZnO–NPs, and Figure 3 displays the EDS spectra of ZnO-NPs, including O, C, and Zn elements. These outcomes confirm the proper synthesis of the ZnO-NPs. All the identified elements by EDS are well-matched with the determined crystalline phase by XRD.

Figure 1.

X-ray Diffraction Pattern of Zinc Oxide Nanomaterials.

.

X-ray Diffraction Pattern of Zinc Oxide Nanomaterials.

Figure 2.

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy Image of ZnO-NPs. Note. ZnO-NPs: Zinc oxide nanomaterials.

.

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy Image of ZnO-NPs. Note. ZnO-NPs: Zinc oxide nanomaterials.

Table 2.

Elemental Analysis of ZnO-NPs

|

Elements

|

ZnO

|

|

Weight (%)

|

| Carbon |

9.45 |

| Oxygen |

13.91 |

| Zn |

76.64 |

Note. ZnO-NPs:Zinc oxide nanoparticles.

Figure 3.

EDS Spectra of ZnO-NPs. Note. EDS: Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy: ZnO-NPs: Zinc oxide nanomaterials.

.

EDS Spectra of ZnO-NPs. Note. EDS: Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy: ZnO-NPs: Zinc oxide nanomaterials.

Antibacterial Activity Evaluation

The growth of Acinetobacter cells was determined with and without ZnO-NPs, CST, CTX, and CIP. Based on the results, CTX and CIP did not exert a notable inhibitory effect on growth while CST and ZnO-NPs showed considerable growth inhibitions in comparison with the control. The MIC of CST and ZnO-NPs was obtained to be 0.5-1 µg/mL and 0.5 mg/mL, respectively, and they inhibited the cell growth in a concentration-dependent manner.

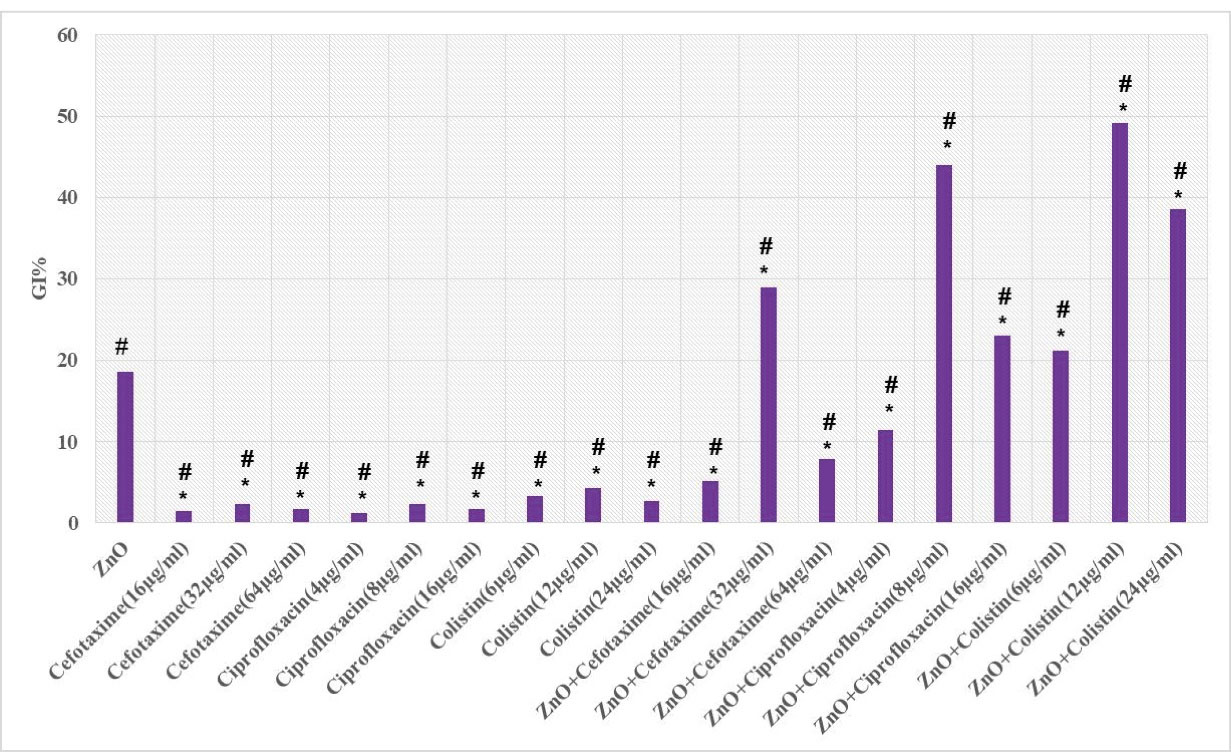

Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 4 represent the mean of GI% of CTX, CIP, and CST (inhibitory and sub-inhibitory concentrations) alone and in combination with a sub-inhibitory concentration of ZnO-NPs (1/2MIC, 0.25 mg/mL) against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter cells. Based on the results, ZnO-NPs could restore the inhibitory activity of CTX and CIP and increase the antibacterial properties of CST. The highest inhibitory activity was obtained at 8 µg/mL CIP, 32 µg/mL CTX, and 0.5 µg/mL CST.

Table 3.

Growth Inhibitory Percentage (GI%) of Pure CTX and CIP or in Combining With ZnO-NPs Against Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Isolates After 24 hours

|

ZnO-NPs Concentration (mg/mL)

|

(µg/mL)CTX Concentration

|

(µg/mL) CIP Concentration

|

|

0

|

16

|

32

|

64

|

0

|

4

|

8

|

16

|

| 0 |

0a |

1.45±0.24a |

2.27±0.32a |

1.67±0.46a |

0a |

1.26±0.33a |

2.37±0.28a |

1.64±0.31a |

| 0.25 |

18.64±0.73b |

15.12±0.40b |

28.92±0.76b |

17.82±0.51b |

19.15±0.35b |

11.45±0.31b |

43.91±0.36b |

23.04±0.67b |

Note. ZnO-NPs: Zinc oxide nanoparticles; CTX: Cefotaxime; CIP: Ciprofloxacin.

Different lowercase letters within a column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Growth Inhibitory Percentage (GI%) of CST Alone or in Combination With ZnO-NPs Against Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Isolates After 24 hours

|

ZnO-NP Concentration (mg/mL)

|

(µg/mL) CST Concentration

|

|

0

|

0.5

|

1

|

2

|

| 0 |

0a |

4.29±0.5a |

2.64±0.43a |

3.24±0.43a |

| 0.25 |

20.76±0.64b |

49.15±1.58b |

38.49±0.85b |

21.11±0.91b |

Note. ZnO-NPs: Zinc oxide nanoparticles; CST: Colistin.

Different lowercase letters within a column show significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Growth Inhibitory Percentage (GI%) of Cefotaxime, Ciprofloxacin, and Colistin Alone or in Combination With ZnO-NPs Against Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Isolates After 24 Hours. Note. ZnO-NPs: Zinc oxide nanoparticles. *Indicates a significant difference compared with the group treated with ZnO-NPs (P < 0.05). #Represents a significant difference in comparison with the group treated with the combination of ZnO-NPs and each of the test antibiotics (P < 0.05).

.

Growth Inhibitory Percentage (GI%) of Cefotaxime, Ciprofloxacin, and Colistin Alone or in Combination With ZnO-NPs Against Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Isolates After 24 Hours. Note. ZnO-NPs: Zinc oxide nanoparticles. *Indicates a significant difference compared with the group treated with ZnO-NPs (P < 0.05). #Represents a significant difference in comparison with the group treated with the combination of ZnO-NPs and each of the test antibiotics (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Acinetobacter spp. is one of the prominent MDRs among bacteria. MDR Acinetobacter is difficult to eradicate and easily spreads in the ICU (5). Therefore, new strategies should be taken into account to treat their infections. Our research focused on the possible synergistic effect of ZnO-NPs in combination with CIP and CTX to restore their antimicrobial properties against resistant Acinetobacter. Furthermore, the concomitant use of ZnO-NPs and CST was checked against multidrug-resistant isolates with the hope of reducing the functional dose of CST, thus diminishing its adverse side effects.

In the current research, a high prevalence of multidrug resistance was observed among the studied Acinetobacter isolates. In other words, all isolates (100%) showed resistance to all main classes of antibiotics usually prescribed for treating infections. This finding is in compliance with the results of Noori et al (2), Ghasemi and Jalal (4), Maraki et al (23), and Vakili et al (24) demonstrating that more than 90% of the obtained Acinetobacter isolates from clinical samples were MDR. Our findings also revealed that all the isolates were completely resistant to CIP, CTX, PIP, MEM, TIC, AM, and AMX/CLV acid. Similar findings were described by Ghasemi and Jalal, Al-Naqshbandi et al, Maraki et al, and Lv et al (4,23,25,26), implying that all the studied isolates were 100% resistant to these antibiotics. Moreover, full susceptibility was observed against CST. In line with our finding, Noori et al, Maraki et al, and Rastegar-Lari et al reported a prevalence rate of 97%, 99.6%, and 100% for isolates that were sensitive to CST, respectively (2,23,27).

It was well-documented that NPs have a broad-spectrum inhibitory effect against a wide range of bacterial pathogens (4,6,7,11,16). In the current research, ZnO-NPs were synthesized by the solvothermal method and well-characterized via FESEM, XRD, and EDS techniques. The antimicrobial study indicated that ZnO-NPs can be effective against the tested MDR Acinetobacter. Considering the obtained results, a direct relationship was observed between the inhibitory effect and concentration of ZnO-NPs against resistant bacteria. Some other researchers reported the dose-dependent antimicrobial manner regarding the NPs of ZnO, Ag, and Cu against Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterococcus faecalis (4,8,11). The minimum inhibitory concentration of the synthesized ZnO-NPs in this study was demonstrated as 0.5 mg/L, which is in agreement with the result of Ghasemi et al (4).

In this research, a sub-inhibitory concentration of ZnO-NPs (0.25 mg/L) in combination with all the examined doses of CIP and CTX could dramatically reduce the resistance of MDR isolates to both antibiotics compared to their pure application (P ˂ 0.005). The highest growth inhibitory level was observed when 8 µg/mL CIP and 32 µg/mL CTX concentrations were separately mixed with ZnO-NPs. These findings are in line with the published results of Ghasemi et al and Isaei et al, representing that ZnO-NPs notably incremented the antibacterial effectiveness of CIP and CTX against MDR A. baumannii and CAZ against resistant P. aeruginosa, respectively (4,11). Likewise, Thati et al and Banoee et al investigated the combined effect of ZnO-NPs (20-45 nm) with diverse conventional antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli (28,29). Furthermore, ZnO-NPs considerably enhanced the growth inhibition activity of CST against MDR Acinetobacter and reduced its functional dose compared to unaided CST. In a similar study, Salman et al recommended that the combination of silver NPs and CST (Polymyxin B) resulted in increased biofilm inhibition activity against P. aeruginosa (30). Such synergistic activities between conventional antibiotics and NPs may result from inhibiting the export of antibiotics through efflux pump blockage or antibiotic entrance enhancement into the cell via bacterial membrane damage (29).

Conclusions

The combined application of ZnO-NPs with CIP and CTX separately restored their antibacterial activity considerably compared to NPs and antibiotics alone against MDR Acinetobacter. Additionally, the inhibitory dose of CST was reduced as a result of the synergistic effect of ZnO-NPs. Therefore, the use of ZnO-NPs can be a novel strategy for removing the limitations of conventional antibiotics and reviving their antimicrobial activity against resistant bacterial strains. However, this finding requires further in vitro and in vivo examination of different resistant bacteria.

Conflict of Interests

None.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by East Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

References

- Fournier PE, Richet H. The epidemiology and control of Acinetobacter baumannii in health care facilities. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42(5):692-9. doi: 10.1086/500202 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Noori M, Mohsenzadeh B, Bahramian A, Shahi F, Mirzaei H, Khoshnood S. Characterization and frequency of antibiotic resistance related to membrane porin and efflux pump genes among Acinetobacter baumannii strains obtained from burn patients in Tehran, Iran. J Acute Dis 2019; 8(2):63-6. doi: 10.4103/2221-6189.254428 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vrancianu CO, Gheorghe I, Czobor IB, Chifiriuc MC. Antibiotic resistance profiles, molecular mechanisms and innovative treatment strategies of Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 2020; 8(6):935. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8060935 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi F, Jalal R. Antimicrobial action of zinc oxide nanoparticles in combination with ciprofloxacin and ceftazidime against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2016; 6:118-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.04.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Elham B, Fawzia A. Colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from critically ill patients: clinical characteristics, antimicrobial susceptibility and outcome. Afr Health Sci 2019; 19(3):2400-6. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v19i3.13 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dadgar M, Tabatabaee Bafroee AS, Minaeian S. The effect of antibacterial synergism of silver nanoparticles with extract of Urtica dioica and Allium hirtifolum against multidrug resistant klebsiella (MDR) isolated from ICU patients. Medical Sciences Journal of Islamic Azad University Tehran Medical Branch 2019; 29(2):131-40. doi: 10.29252/iau.29.2.131 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zeinali Aghdam S, Minaeian S, Sadeghpour Karimi M, Tabatabaee Bafroee AS. The antibacterial effects of the mixture of silver nanoparticles with the shallot and nettle alcoholic extracts. J Appl Biotechnol Rep 2019; 6(4):158-64. doi: 10.29252/jabr.06.04.05 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sanhueza G, Fuentes-Rodríguez D, Bello-Toledo H. Copper nanoparticles as potential antimicrobial agent in disinfecting root canals A systematic review. Int J Odontostomat 2016; 10(3):547-54. doi: 10.4067/s0718-381x2016000300024 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Garcidueñas-Piña C, Medina-Ramírez IE, Guzmán P, Rico-Martínez R, Morales-Domínguez JF, Rubio-Franchini I. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of nanostructured materials of titanium dioxide doped with silver and/or copper and their effects on Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Photoenergy 2016; 2016:8060847. doi: 10.1155/2016/8060847 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- de Souza RC, Haberbeck LU, Riella HG, Ribeiro DH, Carciofi BA. Antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by solochemical process. Braz J Chem Eng 2019; 36(2):885-93. doi: 10.1590/0104-6632.20190362s20180027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Isaei E, Mansouri S, Mohammadi F, Taheritarigh S, Mohammadi Z. Novel combinations of synthesized ZnO NPs and ceftazidime: evaluation of their activity against standards and new clinically isolated Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol 2016; 8(4):169-74. [ Google Scholar]

- Raghupathi KR, Koodali RT, Manna AC. Size-dependent bacterial growth inhibition and mechanism of antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Langmuir 2011; 27(7):4020-8. doi: 10.1021/la104825u [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jones N, Ray B, Ranjit KT, Manna AC. Antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticle suspensions on a broad spectrum of microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2008; 279(1):71-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01012.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Garg A, Pandit S, Mokkapati V, Mijakovic I. Antimicrobial effects of biogenic nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2018; 8(12). doi: 10.3390/nano8121009 [Crossref]

- Sirelkhatim A, Mahmud S, Seeni A, Kaus NHM, Ann LC, Bakhori SKM. Review on zinc oxide nanoparticles: antibacterial activity and toxicity mechanism. Nanomicro Lett 2015; 7(3):219-42. doi: 10.1007/s40820-015-0040-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Baptista PV, McCusker MP, Carvalho A, Ferreira DA, Mohan NM, Martins M. Nano-strategies to fight multidrug resistant bacteria-”A Battle of the Titans”. Front Microbiol 2018; 9:1441. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01441 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ashtaputre SS, Deshpande A, Marathe S, Wankhede ME, Chimanpure J, Pasricha R. Synthesis and analysis of ZnO and CdSe nanoparticles. Pramana 2005; 65(4):615-20. doi: 10.1007/bf03010449 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jalal R, Goharshadi EK, Abareshi M, Moosavi M, Yousefi A, Nancarrow P. ZnO nanofluids: green synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial activity. Mater Chem Phys 2010; 121(1-2):198-201. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2010.01.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moosavi M, Goharshadi EK, Youssefi A. Fabrication, characterization, and measurement of some physicochemical properties of ZnO nanofluids. Int J Heat Fluid Flow 2010; 31(4):599-605. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2010.01.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Patel JB. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017.

- Balouiri M, Sadiki M, Ibnsouda SK. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: a review. J Pharm Anal 2016; 6(2):71-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Perez F, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Decker BK, Rather PN, Bonomo RA. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51(10):3471-84. doi: 10.1128/aac.01464-06 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Maraki S, Mantadakis E, Mavromanolaki VE, Kofteridis DP, Samonis G. A 5-year surveillance study on antimicrobial resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates from a tertiary Greek hospital. Infect Chemother 2016; 48(3):190-8. doi: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.3.190 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vakili B, Fazeli H, Shoaei P, Yaran M, Ataei B, Khorvash F. Detection of colistin sensitivity in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii in Iran. J Res Med Sci 2014; 19(Suppl 1):S67-70. [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Naqshbandi AA, Chawsheen MA, Abdulqader HH. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial pathogens isolated from urine specimens received in rizgary hospital - Erbil. J Infect Public Health 2019; 12(3):330-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2018.11.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lv Y, Xiang Q, Jin YZ, Fang Y, Wu YJ, Zeng B. Faucet aerators as a reservoir for Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a healthcare-associated infection outbreak in a neurosurgical intensive care unit. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2019; 8:205. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0635-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rastegar-Lari A, Mohammadi-Barzelighi H, Arjomandzadegan M, Nosrati R, Owlia P. Distribution of class I integron among isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii recoverd from burn patients. J Med Bacteriol 2015; 2(1-2):1-11. [ Google Scholar]

- Thati V, Roy AS, Ambika Prasad MV, Shivannavar CT, Gaddad SM. Nanostructured zinc oxide enhances the activity of antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus. J Biosci Tech 2010; 1(2):64-9. [ Google Scholar]

- Banoee M, Seif S, Nazari ZE, Jafari-Fesharaki P, Shahverdi HR, Moballegh A. ZnO nanoparticles enhanced antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2010; 93(2):557-61. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31615 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Salman M, Rizwana R, Khan H, Munir I, Hamayun M, Iqbal A. Synergistic effect of silver nanoparticles and polymyxin B against biofilm produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates of pus samples in vitro. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2019; 47(1):2465-72. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1626864 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]